Energy transition

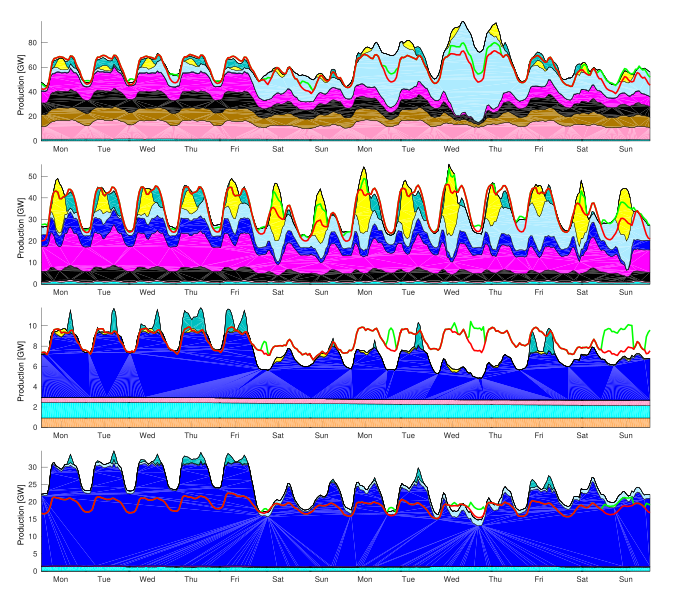

The unfolding energy transition in Europe is changing how we produce our electricity. European countries are transitioning from an old paradigm, where large centralized dispatchable power plants sustain the load and follow its variations, to a new one, where decentralized nonflexible new Renewable Energy Sources (RES)(mainly photovoltaic panels and wind turbines) are producing a significant share of our electricity.

This increasing penetration of renewable energy sources offers to the power system community new challenges to tackle. We focus our investigations on the following topics:

- Integration of RES in the pan-European grid.

- Revenues of power plants in high RES penetration systems.

- Low rotational inertia power systems.

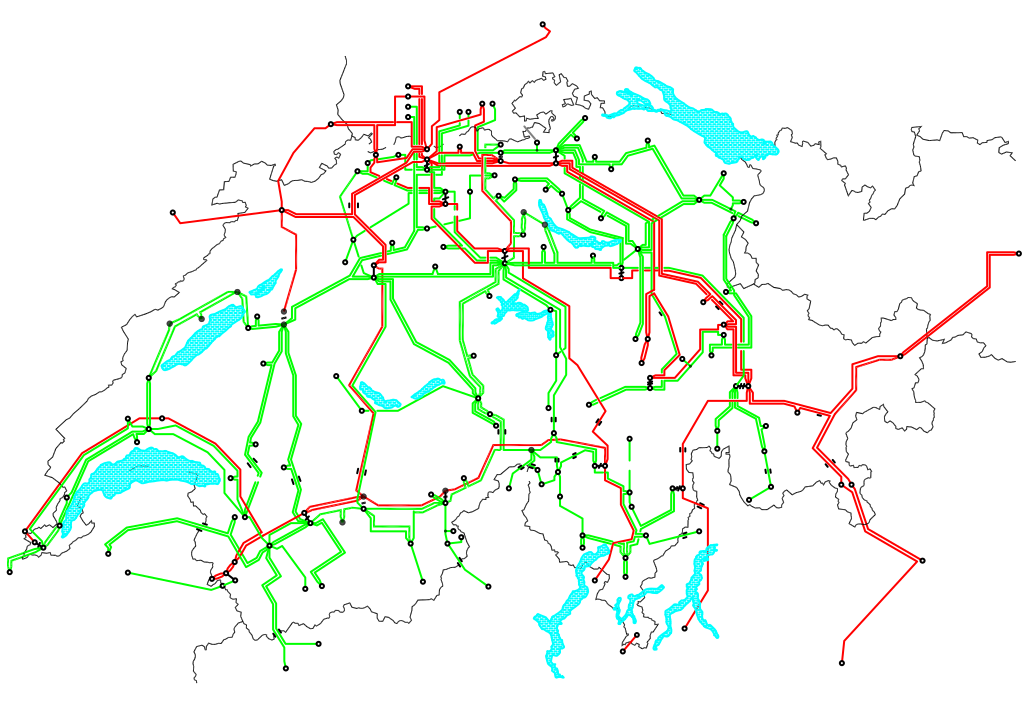

The load must be sustained at any time, more nonflexible new RES implies that more flexibility is asked to dispatchable generators. This flexibility might be obtained through the installation of new storage facilities. Better cooperation of the different agents (power markets, transmission system operators, etc.) and more intensive usage of the grid reduce the amount of flexibility needed. In particular, we show that with optimal power dispatches and more intensive international exchanges in Europe, the existing transmission grid can, with limited enhancements, withstand high RES penetrations [Pag17a, Pag18].

Ultimately the energy transition is driven by future economic prospects. New RES which have negligible marginal costs, drive down the spot electricity prices. Since 2008, the average spot price has been halved. Flexible power plants, which will be needed when the energy transition reaches its mature stage, are currently not profitable enough. In Germany, for instance, gas-fired power plants are mothballed until prices rise. We show that this situation is mainly due to the fact that low ramping rate thermal (e.g. coal-fired) power plants that sometimes produce below their marginal cost are kept in the production mix. This paradoxical situation will last as long as these productions remain [Pag17b].

Conventional generators are large rotating machines, they have rotational inertia which helps to stabilize the grid. A power system is in a stable state if production equals consumption. In reality, there is always a mismatch: if there is a lack (surplus) of production, the system frequency decreases (increases). In the first few seconds after the loss of a large power plant, missing power is obtained by decreasing kinetic energy of the conventional generators. Afterwards, thanks to primary control, frequency usually stabilizes to a slower frequency. Rotating inertia buys time to primary control to settle up, more rotating inertia means more time to react. New RES, which are connected to the grid with inverters, have no rotational inertia. The total system inertia is lower when RES produce significant share of electricity.